What Types of Tasks Are in a Problem-Based Curriculum?

In Peter Liljedahl’s book1, Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics, he describes three types of lessons:

Non-curricular tasks

Highly engaging thinking tasks that are used without concern for curriculum.

Scripted curricular tasks

Curricular tasks that are turned into thinking tasks.

As-is curricular tasks

Curricular tasks that are demonstrated through direct instruction to promote mimicking.

As a teacher wanting to build a thinking classroom, I instantly started to look for tasks. Since my main resource for lessons fell under the type 3 category of tasks, I set out to adapt lessons into thinking tasks (type 2). Liljedahl describes how to do this by thin-slicing, in which educators “create a sequence of tasks that get incrementally more challenging by varying one thing at a time.” Liljedahl pg. 166

Liljedahl recently described this sequence as being convergent since there is one solution path. These lessons worked well with my students and helped build thinking in my classroom. I write about how I developed lessons here in Building a Thinking Classroom with a Traditional Textbook.

During my second year of implementing BTC, my school adopted a problem-based curriculum. Many lessons in a problem-based curriculum consist of thinking tasks and seem to fall under type 2 (scripted curricular tasks), rather than type 3, where tasks are demonstrated by the teacher and mimicked by the students. Although the problems are not in a thin-sliced sequence, they tend to follow this description of scripted curricular tasks.

Script curricular tasks such that you; (Liljedahl pg 35)

Begin by asking a question about prior knowledge.

Then ask a question that is an extension of that prior knowledge.

Then ask students to do something without telling them what to do.

Here is an example from CPM Education Program Core Connections Algebra 2 text.2

Begin by asking a question about prior knowledge.

Task 1

Task 2

Then ask a question that is an extension of that prior knowledge and ask students to do something without telling them what to do.

Task 3

While building a thinking classroom, it is a good idea to give these problems one at a time or each task separately so groups can focus on one problem or problem set and not worry about the time it will take to finish all of the tasks. Once my students became more comfortable with thinking, they had no problem working out of the textbook and I could assign the problem sets out of the book instead of assigning the problems verbally and one at a time. In groups, one student naturally took on the role of reading the problem to the group and making sure the group started working.

The first chapter of each course in CPM is full of rich non-curricular tasks, so students became used to thinking and working in groups before we dug into the curriculum in Chapter 2.

Other problem-based curricula also tend to follow this scripted curriculum task sequence. Here is a lesson from Algebra 1 Illustrative Mathematics. IM is a K-12 open resource and available for free through Kendall Hunt.

Begin by asking a question about prior knowledge.

Task 1

Then ask a question that is an extension of that prior knowledge.

Task 2

Then ask students to do something without telling them what to do.

Task 3

As students work through the sequence of problems, it is a good idea to have hints and extensions ready. You will want hints for the groups that can’t quite make the jump between problems and extensions for the groups that need more challenging questions. Both CPM and Illustrative Math attend to this by having extra problems in the lessons. CPM calls these non-core problems.

In this series of problems, only problems c and d are core problems, or problems that attend to the curricular goal. Problems a and b could be used as hints, and problems e and f could be used as extensions.

In IM, each lesson offers a section that naturally extends the lesson.

Other types of problems in problem-based curricula tend to be less scripted and thought of as rich thinking tasks. Mathematics Tasks for the Thinking Classroom, Grades K-53, lists qualities of a good thinking task.

It has a low floor.

It has a high ceiling.

It is novel or something the students haven't seen before.

Rich thinking tasks are divergent since they have multiple solution paths and can be curricular in nature. These types of tasks generally show up to introduce or review a concept. Here is an example of a CPM task in Core Connections Geometry4 that helps students practice finding the area of sectors and length of arcs.

I love these types of tasks because I enjoy seeing all of the different ways students think about the problem. As a teacher new to assigning rich tasks, it may be helpful to have a plan for hints and extensions. I might introduce this problem verbally to get the students started. For instance, tell the story of Zoe’s goat and write down the dimensions of the barn and explain that the rope is 10 meters long. Then I would let the students start working. Giving the problem verbally helps students become interested in the problem and only think about one answer at a time. As students work, offer hints:

Would a picture help you think about the problem?

What information do you know?

What is the area of the grass the goat could eat if the rope was tied in the middle of the yard?

How does the barn affect the grass that the goat can eat?

As groups find the area of the sector of the first problem, extend the problem by having groups find the area of the grass covered when the rope is 30 meters. This adds a new layer of difficulty because the rope will extend past the barn on one side and creates a new sector.

Some groups may be able to make the jump, and some may need some hints to help them. What makes this task rich is that it includes many ways to extend student thinking. The curricular goal of finding the area of a sector is met when students answer part a, and parts b-d offer good extension problems with a high ceiling.

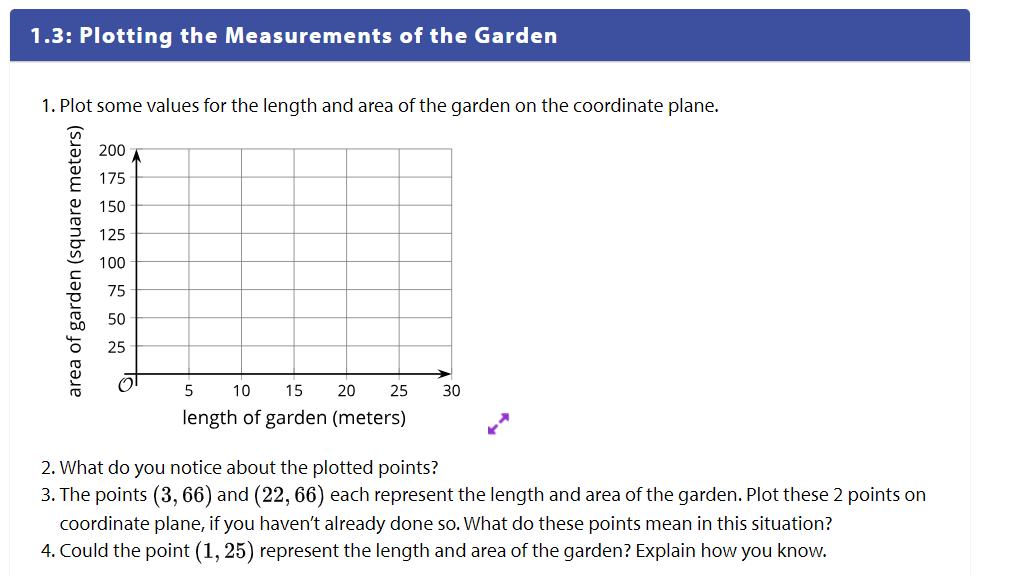

In this IM lesson, students are introduced to quadratic relationships.

Again this type of problem can be given verbally. I would tell the story of Noah and his garden. The only information the students need to keep track of is the 50 meters of fencing around the garden. The low floor of this problem allows students to engage quickly. Here are some hints to have ready for the groups.

How do you know the length and width will make a 50-meter fence?

What is the area of the garden?

Are there other dimensions that will produce a 50-meter fence?

What is the largest possible area?

How do you know if that is the largest area?

How could you organize your results?

After students think they have found the largest area, give them the next task.

Graphing the results extends the learning and focuses the students on a new type of relationship that is not linear. Making a graph from their drawings may be a jump for students. They may need a few hints to help them.

Is there a systematic way to record your results that would help you make the graph?

If the length is 5, what is the width? What is the area?

What is the area if the length is 10?

Although lessons are written with thinking tasks in a problem-based curriculum, it is important to know your students and be prepared to help or challenge students while they are working on the tasks. As with any resource, you will need to modify it slightly to best fit your students.

Liljedahl, Peter. Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics, Grade K-12. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2021.

Core Connections Algebra 2. © 2024 CPM Educational Program. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Peter Liljedahl, Maegan Giroux, Mathematics Tasks for the Thinking Classroom, Grades K-5: Corwin, 2024

Core Connections Geometry. © 2024 CPM Educational Program. All rights reserved. Used with permission