After 9 years of teaching, I made the move from teaching middle school to high school. At the time, I needed a change and was excited for the move but not sure about the textbook from which I would be teaching. I had been using an inquiry-based middle school curriculum that I loved. Now I would be teaching from a traditional textbook. I told myself that I could develop inquiry-based lessons even with a traditional textbook, but I instantly fell back into the old routine of I do, we do, you do. Disappointed in the way I was running my class, I looked for ways to adapt textbook lessons to be more inquiry-based. I landed on a system of rearranging the examples in the book.

Start with the story problem example

Have students develop any definitions or algorithms

Have students use new information to solve the example problems, also known as thin slicing

Sometimes I would switch steps 2 and 3 depending on the lesson.

This system increased student discourse and thinking, but there was still a piece missing. I couldn’t quite put my finger on it until I read Peter Liljedhal’s book, Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics, Grade K-12. 1

The book caused me to rethink group size and configuration. I originally had students working in groups of four at their desks. I saw a big increase in student engagement and productivity when students worked in random groups of three at whiteboards.

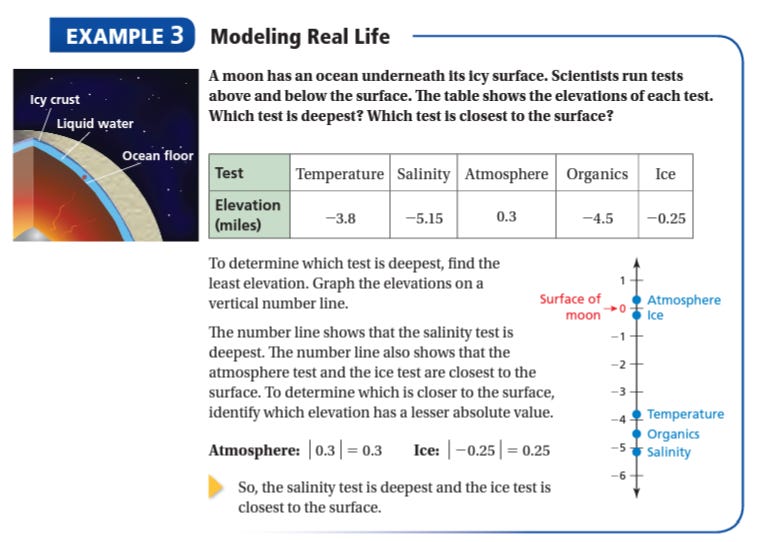

Most traditional textbooks start with the definitions and then work through a series of examples that increase in difficulty. Here is an example of how I would rearrange a 7th grade lesson on absolute value in Big Ideas2. Generally, the last example problem in the textbook is a story problem that encapsulates the learning from the lesson. I like to switch the lesson around and start with the last example problem.

The only problem with the story problem in the book is that it shows the explanation of how to solve it. So, when I assign it to students, I cut out the explanation. This changes the story problem to a thinking task.

I start the lesson by assigning random groups and having students move to the whiteboards. Then I present the class with the story problem.

Since there is a context with the problem, students will be able to answer it even though they don’t have formal knowledge of absolute value. To keep students in flow, I like to ask them questions like:

What is the elevation of the surface?

Why are there positive and negative numbers?

How can you show your thinking?

How far away from the surface was the test taken?

By answering the story problem, students will start to talk about the distance from the surface or zero. This is a nice way to introduce absolute value without formally defining it yet and a great place to consolidate the students’ thoughts as a class.

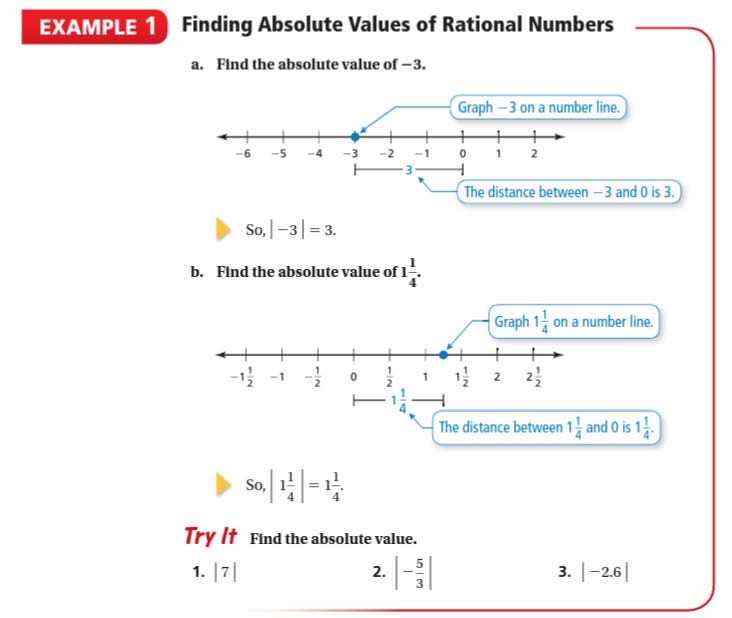

Once students have explained their answers, I go back to the beginning of the lesson where the key concepts are introduced.

But instead of giving the students the definition, I ask them which number is farther away from zero, 4 or -4. Now that students have explored the idea of absolute value, they have a need for the term and notation, so it is appropriate to introduce the term absolute value and for students to write down the official definition.

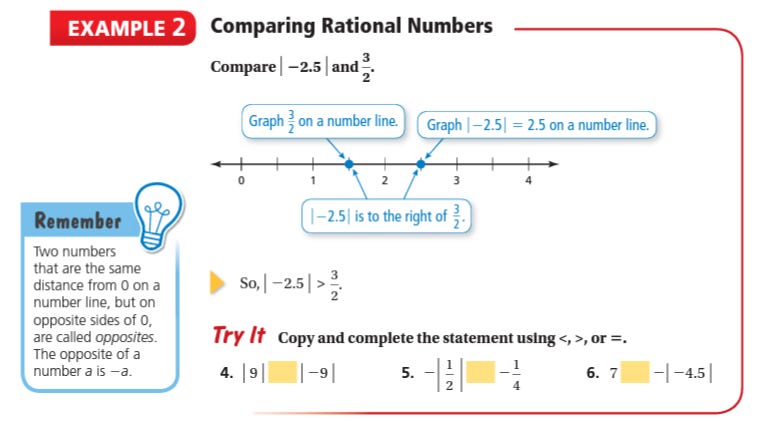

In the last step of this process, I choose some of the remaining example problems with increasing difficulty for the groups to solve. Liljedahl calls this thin slicing. Students perform the tasks at the whiteboards and then we consolidate their work.

I have started lessons by just thin slicing each example and skipping the story problem. While students can still perform the calculations correctly, it’s more meaningful and relevant for students when they have an opportunity to connect a new math concept to an authentic context. Without working on the story problem first, students missed out on an opportunity to work on a thinking task.

Liljedahl, Peter. Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics, Grade K-12. Thousand Oaks, CA : Corwin, 2021.

BIG IDEAS MATH. Modeling Real Life - Grade 7 Common Core Edition. National Geographic School. 2018

That’s right! Well explained! Sometimes I have to go looking to find the the right story problem. But it’s worth the search!

Thanks for thinking this through and sharing!

That’s right! Well explained! Sometimes I have to go looking to find the the right story problem. But it’s worth the search!

Thanks for thinking this through and sharing!